(english below)

Er zijn niet veel positieve aspecten aan de pandemie, die ons leven nog steeds beheerst. Wat ik wel intrigerend vind, is om te zien hoe kunstenaars hier elk op hun eigen manier mee omgaan.

Als je in de geschiedenis van het leven van een componist (of beeldend kunstenaar) duikt, ontdek je automatisch ook waarom die schreef wat hij schreef, als versterking van of afzetting tegen.

Mijn gps start aan het begin van de 20ste eeuw, de aanvang van een periode waar we op zijn zachtst uitgedrukt van kunnen zeggen dat de maatschappelijke uitdagingen en het menselijke leed enorm waren.

Mijn generatie, opgegroeid in het westen, werd echter nooit onderworpen aan oorlogen of andere levensbedreigingen. We leefden nooit in een situatie waar kunst dreigde vernietigd te worden of waar kunst absoluut noodzakelijk was om ons gedachtengoed te beschermen. We dobberden in de luxe van ruimte te hebben, te nemen en te vullen.

Tot nu. Het is uiteraard geen oorlog, maar toch zie je heel duidelijk dat al wie bezig is met kunst en creëren echt wel zeer diep emotioneel en intellectueel getroffen wordt door deze wereldwijde crisis. De term ‘Covid art’ duikt overal op en wijst (voor mij althans) op de eerste keer dat wij meemaken dat onze luxueuze ruimte plots intellectueel bezet gebied wordt.

Ikzelf maak uiteraard geen nieuwe kunst in deze tijd, ik reproduceer, maar alle uitvoerders zullen het met me eens zijn dat bepaald repertoire dichter bij een state of mind staat dan ander.

Zo was voor mij Still time III(1987) van Toshi Ichiyanagi een soort van evenwichtsoefening in de tijd, die er plots heel anders uitzag. De titel fluistert me in dat we ons geen zorgen hoeven te maken en letterlijk beter even stilstaan tot alles overwaait, maar om één of andere reden zet mijn verbeelding vaak een vraagteken achter diezelfde titel, wat dan weer blootlegt hoe deze pandemie onze tijd beknibbelt en vertroebelt.

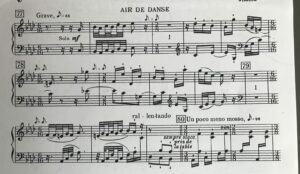

Still time III is een versie voor harp (van de componist zelf) van Still time II wat hij oorspronkelijk componeerde voor Kugo harp. Je hoort een klok die tikt en tijdens het werk in 2 versnellingen gaat, opnieuw(voor mij persoonlijk) een grote, enigszins troostende symboliek voor de voorbije periode.

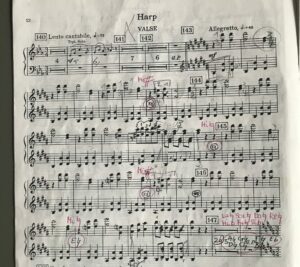

Aan de zeer brede ligging van de arpeggio’s, de diepe tessituur en de niet zo evidente chromatiek, merk je dat het werk niet oorspronkelijk gedacht is voor harp, maar juist die tegenstelling in tijd -tussen de oude Kugo harp en deze versie voor pedaalharp- geeft het stuk een onsterfelijke vorm.

Ichiyanagi is zeker een componist die zich heel bewust door zijn tijd liet beïnvloeden. Zijn Japanse roots vormen duidelijk de basis voor zijn inspiratie in zijn oeuvre (de lijst werken voor Japanse traditionele instrumenten is trouwens indrukwekkend) maar experimenten met technieken uit het nu zijn hem zeker niet vreemd.

Zijn studies aan Juilliard leidden hem naar het podium van de avant-garde muziek (eind jaren 1950-begin jaren 1960) dat hij samen met John Cage en Yoko Ono vulde.

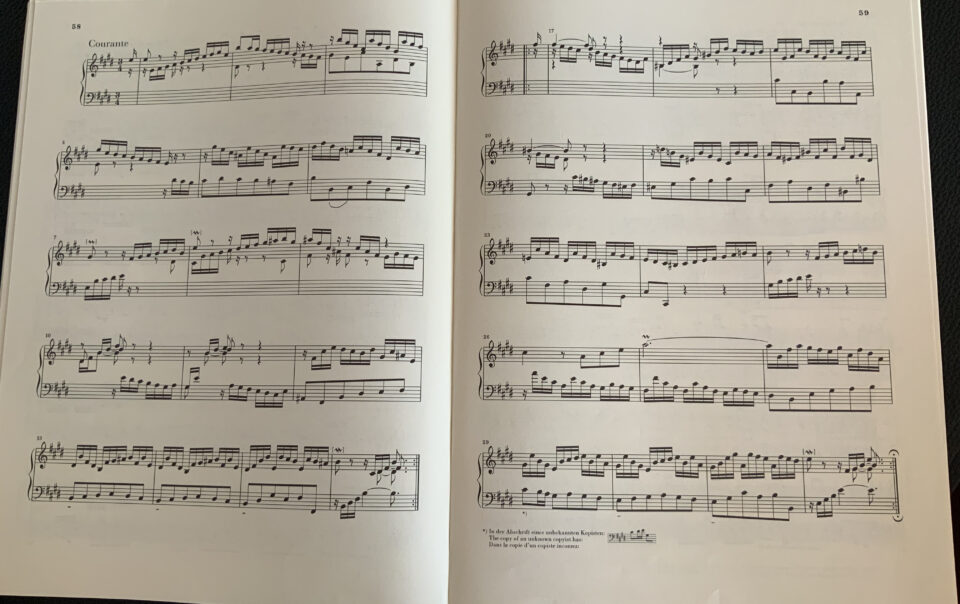

Zijn kijk op muziek en vooral muzieknotatie is boeiend. Zo maakte hij enkele scores die muzikaal zeer abstract zijn, maar die als statement bijzonder sterk overkomen.

In 1960 publiceerde hij IBM for Merce Cunningham, dat gebaseerd is op de eerste computerkaarten die IBM uitbracht.

In zijn ‘Music for electric metronome’ gebruikt hij nummers als instructie voor de reproductie van geluid volgens kansberekening.

Hoe begin je trouwens aan het maken van kunst, aan het schrijven van muziek op het moment dat de wereld 1 groot slagveld is, dat de atoombom je hele culturele verleden heeft opgeblazen? Als ik naar deze grafische partituren kijk, zie ik een kunstenaar die zich probeert te reorganiseren, het stof van de wonden blaast en een basis zoekt om verder te gaan.

Het belang van deze ‘heropstart’ in kunst werd afgelopen jaar in het MoMa in New York prachtig in beeld gebracht tijdens de tentoonstelling: ‘Drawing, from a Starting Point of Zero’

Enkele van Ichiyanagi’s scores zijn trouwens terug te vinden in de online catalogus van dit museum.

Luister je naar zijn muziek, kunnen we alleen maar zeggen dat hem dat gelukt is: hij heeft zijn kunst heropgebouwd en doorgegeven aan de volgende generatie.

“Most of the boundaries are lost. I don’t know whether that is a good thing.”

Toshi Ichiyanagi

There are not many positive aspects to the pandemic, that is still controlling our lives. However, what intriges me are the different ways in which each artist approaches this crisis differently.

When one starts delving in a composer’s live, one automatically discovers the reasons why he wrote what he wrote, as a consolidation or an impeachment.

My gps starts at the beginning of the 20th century, which is the start of a period of great social turmoil and immense human cost.

My generation, born and raised in the west, was never imposed to war or other life threatening situations. We never lived a period in which art was at risk of being destroyed or where art was a necessity to protect our mental legacy. We float on the luxury of taking our own space and filling it the way we want.

Until now. Off course there is no war going on, but you can see very clearly that everyone who is into art or creating in whatever way is strongly stricken emotionally as wel as intellectually by this worldwide crisis.

The terminology ‘Covid art’ was born and points out (at least for me personally) that our space to create is being invaded for the first time and we feel like intellectual hostages.

Obviously, I myself do not produce new art, I reproduce, but all performers will agree that some repertoire feels closer to a state of mind than other.

For me Still time III(1987) by Toshi Ichiyanagi was a kind of exercise in balancing time. Time, all of a sudden, had taken a different dimension.

The titel confided in me, that we didn’t need to worry, that it probably was a good thing to literally stand still and wait till the danger blows over, but for some reason my imagination put a question mark behind the titel, what revealed the scary finding of the way this pandemic obfuscates and skimps our time.

Still time III is a version for harp solo (by the composer himself) of Still time II, which he originally wrote for Kugo harp. What you hear is a clock ticking and changing into 2 different speeds during the piece. Again (for me personally) a consoling symbolism of the past period.

The very wide emplacement of the arpeggio’s, the leaps into the low register and not so apparent use of chromatics, makes it clear that the piece was originally not imagined for harp, but precisely this opposition in time -between the ancient Kugo harp and this version for pedal harp- gives this piece it’s immortality.

Ichiyanagi is definitely a composer who gained his inspiration from his own time. His Japanese roots are clearly the core of his oeuvre (he has an impressive list of works for traditional instruments) but experimenting with new techniques was not an exception either.

His education at Juilliard showed him the way to the the avant- garde music scene(late 1950s-early 1960s). Together with John Cage and Yoko Ono he performed on many stages from the States to Japan.

His approach to music and especially music notation is extremely intriguing. Some of his scores are utterly abstract, but by contrast highly strong as a statement.

In 1960 he published IBM for Merce Cunningham, based on early IBM computer cards

In his ‘Music for electric metronome’ he uses numbers as instructions for sound, based on chance and interpretation.

How does one start producing art, writing music at a time where the world has become killing ground, where the atomic bomb has swept away your entire cultural history? When I look at these graphic compositions, I see above all an artist that tries to reorganize himself, who tries to heal the wounds and searches for a new starting point.

The importance of this ‘relaunch’ in art was subject of the wonderful exhibition: ‘Drawing, from a Starting Point of Zero’ at the MoMa in New York. In fact, some of Ichiyanagi’s scores are on display in this museum’s online catalogue.

Listening to his music we can only agree that he has succeeded: he has re-established his art and has passed it on to the next generation.